Drainage System of India

The drainage system of India is a vast network of rivers and their tributaries that play a vital role in shaping the country’s geography and supporting life. Over the period of time, it not only shaped the physiological feature of India but also added a cultural dimension to a number of civilisations in Indian subcontinent such as Indus Valley civilisation, Ganga Valley or Vedic Civilisation in the north and Chalcolithic civilisations and Megalithic civilisations in Godavari and Krishna river basins to Cauvery and Periyar river basins in the south, in ancient times, till the industrialisation in the modern times.

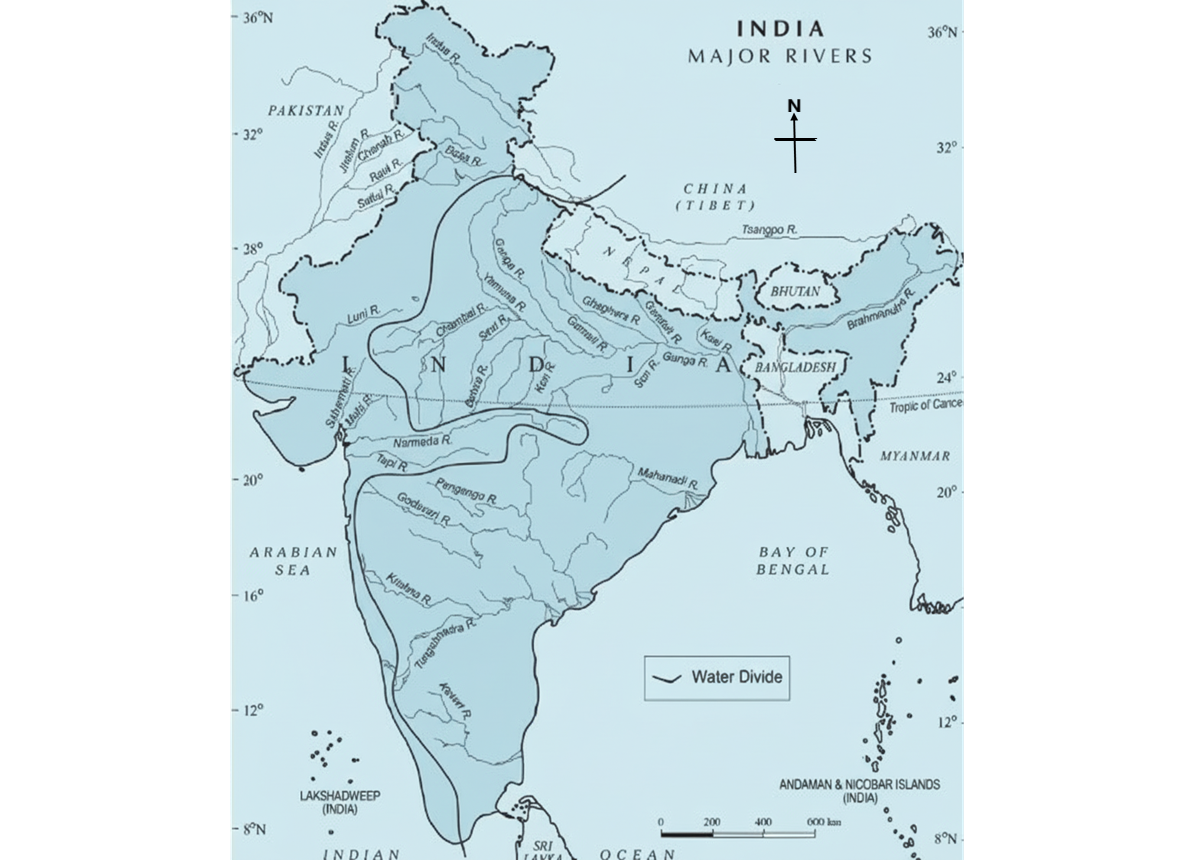

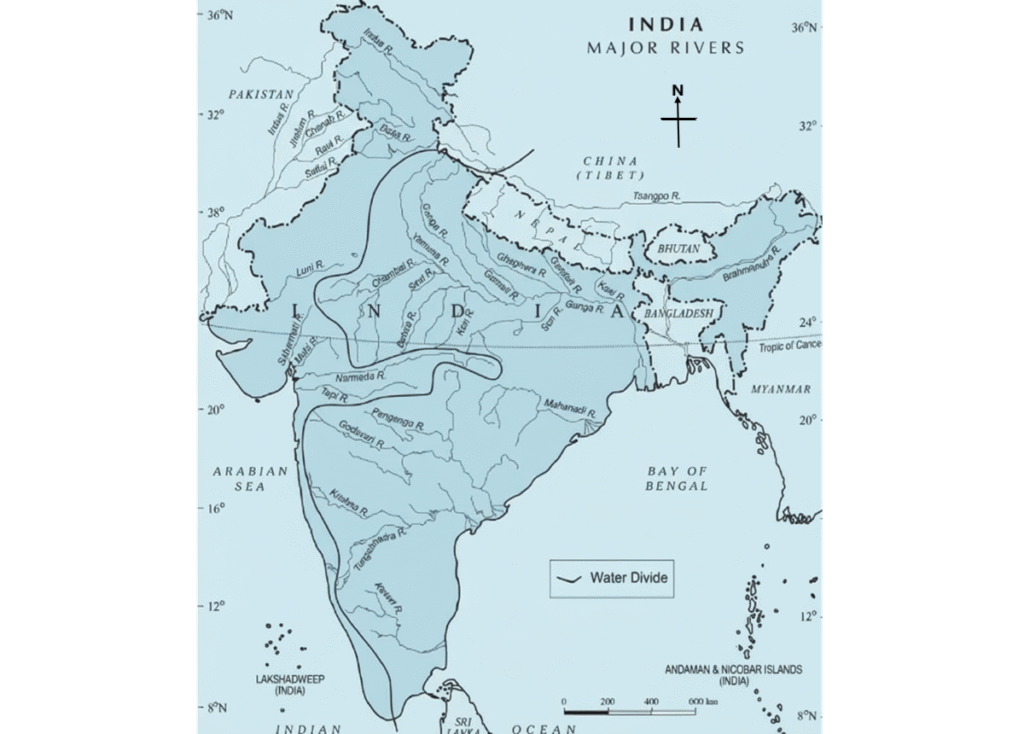

The Drainage System of India is broadly divided into two major systems — the Himalayan rivers and the Peninsular rivers. The Himalayan rivers, such as the Ganga, Indus, and Brahmaputra, are perennial and fed by glaciers, while the Peninsular rivers like Godavari, Krishna, and Mahanadi are rain-fed and seasonal. Together, they sustain agriculture, provide drinking water, aid transportation, and support biodiversity, making the drainage system a crucial element of India’s natural and economic framework.

Table of Contents

Drainage System: Definition and related terms

- Drainage: Refers to the movement of water through well-defined channels, forming a network of interconnected rivers and streams.

- Drainage system: A network comprising the head-water or source, main river course, tributaries, and distributaries. The drainage system of India is an extensive arrangement that regulates surface water flow, shaping the country’s physiography and ecology.

- Function of a drainage system: Describes how surface water travels across the land via rivers and basins, determining how water is transported from higher elevations to larger water bodies.

- Factors influencing drainage patterns:

- Slope or topographic gradient: The inclination of land controlling water flow.

- Geological structures: Features like folds and faults affecting river courses.

- Rock composition (geological structure): Determines erosion and channel formation.

- Climatic and hydrological variations: Seasonal rainfall and water availability.

- Catchment area (water volume): Region contributing water to the river.

- Flow velocity: Speed at which water moves through channels.

These factors collectively define the drainage pattern, controlling water distribution in river basins.

- Head-water or source: The origin of a river, which may be a lake, glacier, spring, or stream.

- Catchment area or watershed: The region from which a river collects water from tributaries, streams, and groundwater.

- Drainage basin: The total area drained by a river and its tributaries; synonymous with catchment area in a collective sense.

- Types of drainage basins:

- Exorheic (open drainage): Rivers discharge into seas or oceans; includes most major Himalayan and Peninsular rivers of India.

- Endorheic (closed drainage): Water retained within the basin, draining into lakes or swamps; examples: Lower Chambal Basin, Sambhar Basin, Loktak Lake Basin, Rann of Kutchh (Luni River), Thar Basin (Ghaggar-Hakra), Tsokar and Tsomoriri Lakes. Large global examples: Caspian and Aral Seas.

- Arheic (arid drainage): Found in deserts with low inflow and high evaporation; examples: Luni River in Rann of Kutch, Ghaggar-Hakra in the Thar Desert.

- Watershed divide: A ridge or boundary separating runoff from one drainage basin to another; large rivers have extensive basins, smaller streams have smaller watersheds.

- Perennial rivers: Rivers with continuous water supply from glaciers and rainfall throughout the year, e.g., Himalayan rivers.

- Non-perennial rivers: Depend on seasonal rainfall or underground springs; low flow and seasonal inundation, typical of Peninsular rivers.

- Understanding these classifications is essential for managing the drainage system of India effectively.

Classification of the Drainage System of India

The Drainage system of India can be classified in several ways depending on its outlet, geological characteristics, and origin of the river systems.

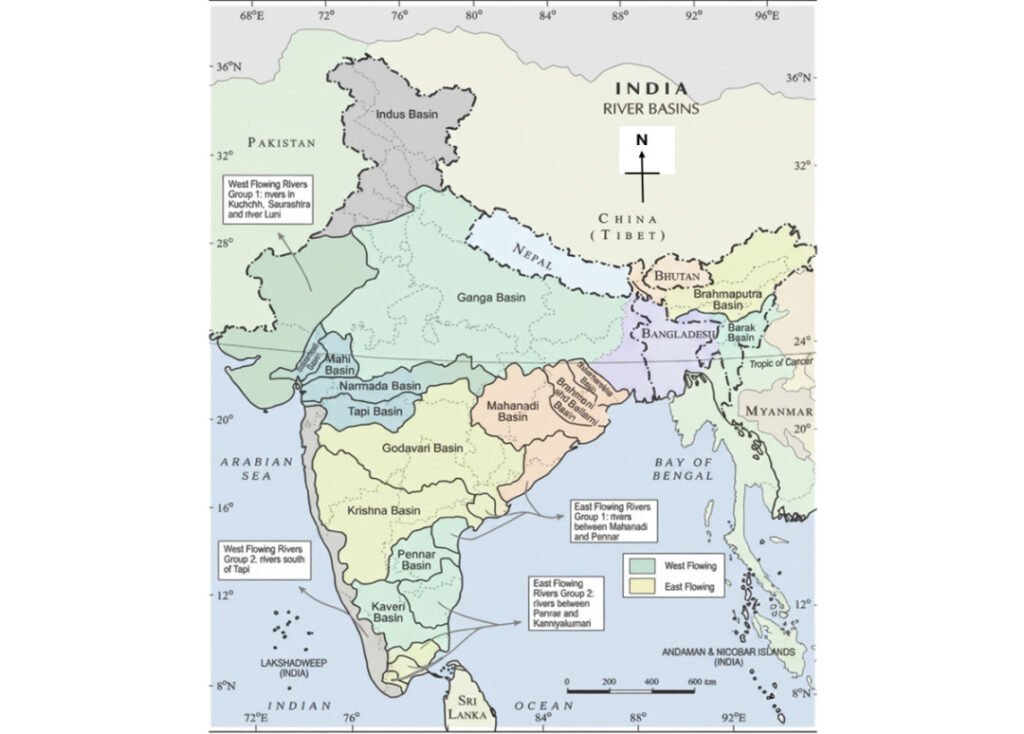

Classification is based on the Outlet of drainage:

- Arabian Sea Drainage– Covers approximately 23% of India’s total drainage area, including rivers such as the Indus, Narmada, Tapi, Mahi, and Periyar.

- Bay of Bengal Drainage-Covers approximately 77% of India’s total drainage area and includes major rivers such as the Ganga, Brahmaputra, Mahanadi, and Krishna.

- Inland Drainage– A small proportion, mainly in arid regions of Rajasthan and Ladakh, forms inland drainage basins.

Classification based on Catchment area size:

The drainage system of India can be categorised by the size of the water collected in river basins.

- A river basin is considered the fundamental hydrological unit for planning and development of water resources

- India has 12 major river basins with a catchment area of 20,000 km² or more.

- The total catchment area of these major rivers is approximately 25.3 lakh km².

- The Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna basin is the largest, with a catchment area of about 11.0 lakh km², accounting for over 43% of the total catchment area of all major rivers in India.

- Other major river basins with catchment areas exceeding 1.0 lakh km² include Indus, Mahanadi, Godavari, and Krishna.

- There are 46 medium river basins with catchment areas ranging between 2,000 and 20,000 km².

- The total catchment area of medium river basins is roughly 2.5 lakh km².

- Most major river basins, and a significant number of medium basins, are inter-state, covering about 81% of India’s geographical area.

classification is based on physiographic origin:

Drainage system of India based on origin can be categorised into two broad groups:

- Himalayan Drainage System

- Peninsular Drainage System

The Central Highlands which constitute Malwa plateaus and rift valleys of Vindhya Range and Satpura Range, in which Narmada and Tapi flow, act as a horizontal geographical divide between the Northern and Southern drainage system. Thus, uniquely contrast the concordant (sequent) which is particularly observed in southern rivers (with some features observed in Himalayan rivers), and discordant (insequent) mostly observed in Himalayan River system (with some features observed in peninsular rivers, such as superimposed and rejuvenated features).

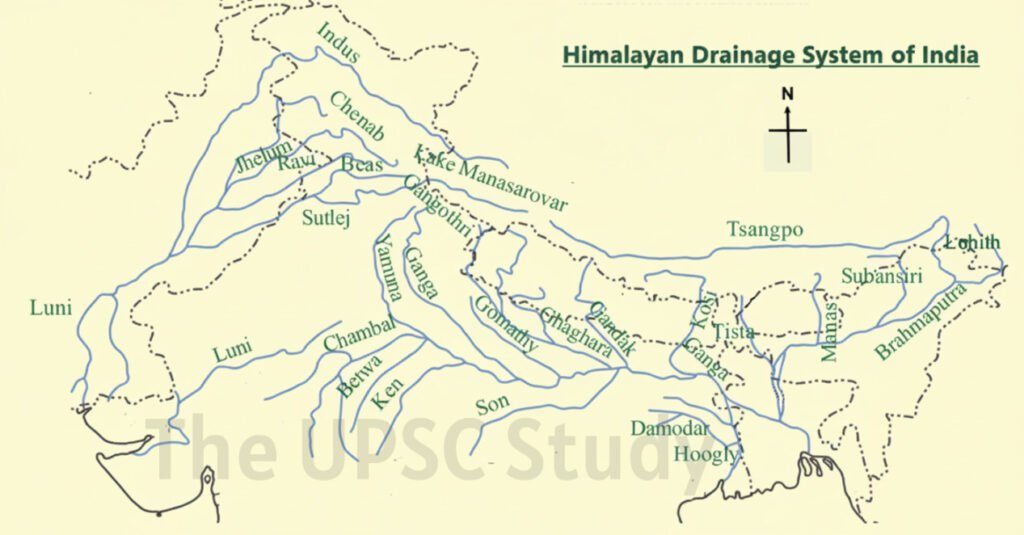

Himalayan Drainage System of India

Drainage System of India– North

The Himalayas play a crucial role in shaping the drainage system of India in North, as most of the region’s major rivers originate from these mountains or beyond them. These rivers, unlike those in southern India, continue to deepen their valleys rapidly through erosion. The eroded materials or sediments are transported from the mountains to the plains and seas, where they are eventually deposited. This deposition occurs because the river’s velocity decreases upon entering the plains and deltas, owing to the lack of steep slope.

The Great Northern Plains were formed by the continuous deposition of silt brought down by these Himalayan rivers. Interestingly, some rivers of the Himalayas are older than the mountains themselves. When the Himalayas began to rise due to tectonic uplift, these ancient rivers simultaneously cut downward through the rising terrain, carving out deep gorges and valleys. As a result, sections of these river valleys are extremely deep; for instance, the Indus Gorge near Bunji (Jammu & Kashmir) is approximately 5200 metres deep. The Sutlej and Brahmaputra rivers have also formed similar spectacular gorges.

The Himalayan drainage system of India can be classified into three primary sub-systems:

- Indus River System – includes the Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej rivers.

- Ganga River System – comprises the Ganga and its tributaries such as Ramganga, Ghaghra, Gomti, Gandak, Kosi, Yamuna, along with its southern tributaries Son and Damodar.

- Brahmaputra River System – includes Dibang and Lohit rivers in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, Tista in Sikkim, West Bengal, and Bangladesh, and Meghna, which drains the northeastern part of Bangladesh.

Evolution and characteristics of the Northern Drainage System

- Originally, a single river known as the Shivalik or Indo-Brahm River is believed to have flowed from Assam to Punjab and then into Sindh.

- Before the formation of the Himalayas, northern India sloped northwestward, draining into the Tethys Sea (modern Arabian region/Sindh).

- The Proto-Ganga and Proto-Brahmaputra, collectively called the Indo-Brahm or Siwalik River, initially flowed westward into this sea. Geological evidence, including similar fossil fauna in the Potwar Plateau and Siwalik Hills, supports the existence of these ancient west-flowing rivers during the Tertiary Period (66–2.58 million years ago).

- About 50–40 million years ago, the Indian Plate collided with the Eurasian Plate, giving rise to the Himalayas.

- This tectonic collision uplifted the northern crust and caused an eastward tilt of the Peninsular Craton.

- The uplift created a depression known as the Indo-Gangetic Trough, a new lowland extending eastward.

- Following this event, rivers began to reorganise their courses, redirecting their flow from west to east.

- Consequently, the Ganga–Brahmaputra system became captured by this new trough and began flowing into the Bay of Bengal.

- This redirection ultimately led to the formation of the Sundarban Delta, the largest delta in the world.

- Today, due to the eastward tilt of the Indian landmass, most rivers flow into the Bay of Bengal, while a few, such as the Narmada and Tapi, flow westward.

- The Potwar Plateau (Delhi Ridge) serves as a water divide between the Indus and Ganga systems.

- The Malda Gap depression further assists in directing the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers eastward towards the Bay of Bengal.

- The Himalayan rivers are primarily antecedent (discordant type), meaning they predate the mountain uplift, and are perennial in nature, maintaining flow throughout the year due to glacial and rainwater sources.

Indus River System

The Indus River System, an essential part of the Drainage system of India, originates (head water) from the glaciers of Mount Kailash near Lake Mansarovar in Tibet at an elevation of about 5,180 m. Flowing north-westward, it enters India in the Ladakh region of Jammu and Kashmir, where it receives the Zaskar, Shyok, Nubra, and Hunza tributaries and flows through Gilgit and Baltistan in the mountains of Attock before entering Pakistan, where it is joined by tributaries Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chenab, and Jhelum, the Panjnads, at Mithankot in Pakistan. Kabul and Khurram are west bank tributaries from Afghanistan. The total length of the Indus River is approximately 2,880 km, of which about 1,114 km flows through India.

Tributaries of the Indus River System

The principal tributaries of the Indus on the Indian side are:

- Jhelum: Originates from the Verinag Spring at the foothills of Pir Panjal, flowing through the Wular Lake in India and joining the Chenab near Jhang in Pakistan.

- Chenab: Formed by the union of two streams, the Chandra and the Bhaga (Chandra-Bhaga) near Keylong in Himachal Pradesh. about 1180 km flow in India. Salal, Baglihar and Dui Hasti Dams are on this river.

- Ravi: Rises near Kullu Hills, from Rohtang pass, in Himachal Pradesh and joins the Chenab after flowing past Chamba valley

- Beas: Originates from Beas Kund near Rohtang Pass and merges with the Sutlej in Punjab.

- Sutlej: The longest of the five tributaries, it rises from Rakshastal near Mansarovar in Tibet and enters India through Shipki La in Himachal Pradesh, then enters Punjab. Also known as Langchenkhambab in Tibet. before entering the Punjab plains is on Sutlej river.

The Indus and its tributaries are crucial for irrigation through the extensive canal systems constructed under the Indus Water Treaty.

The Drainage system of India, through the Indus basin, significantly influences north-western India’s agriculture, especially in Punjab and Haryana.

Ganga-Brahmaputra System:

Ganga River System

The Ganga River System, one of the major components of the drainage system of India, originates as the Bhagirathi,the head-water, fed by the Gangotri Glacier, and meets the Alaknanda, begins at the Satopanth glacier near Badrinath, at Devaprayag in Uttarakhand. Emerging from the mountains at Haridwar, it enters the plains.

Vishnuprayag (Alaknanda-Dauli Ganga), Nandprayag (Nandakini-Alaknanda river), Karnaprayag (Alaknanda-Pindar), Rudraprayag (Mandakini-Alaknanda), and Devprayag (Bhagirathi-Alaknanda) are the confluence point of rivulet tributaries of Ganga, known as Panch Prayag.

The Ganga receives numerous Himalayan tributaries such as the Yamuna, Ghaghara, Gandak, and Kosi. The Yamuna, rising from the Yamunotri Glacier, runs parallel to the Ganga before merging with it at Allahabad (Prayagraj). Rivers like the Ghaghara, Gandak, and Kosi, originating in the Nepal Himalayas, cause annual floods but also replenish the fertile alluvial soils of the northern plains.

From the Peninsular uplands, the Chambal, Betwa, and Son join the Ganga, though they are smaller and carry less water.

Strengthened by its tributaries, the Ganga flows eastwards to Farakka in West Bengal, the north most part of the Ganga delta, where it bifurcates into the Bhagirathi-Hooghly branch flows southwards over Kolkata, while the main channel continues into Bangladesh as the Padma, joining the Brahmaputra (Jamuna) and later the Meghna, forming the vast Sundarban Delta.

Major right bank tributaries are Yamuna and Son. Major left bank tributaries are Ramganga, Gomati, Ghaghara, Gandak, Kosi, and Mahananda.

The Ganga basin of 2525km covers parts of Uttarakhand (110 km), Uttar Pradesh (1,450 km), Bihar (445 km), and West Bengal (520 km), it is the largest river system in India by length. The river holds immense religious and economic significance, forming the core of the Drainage system of India in the north.

Gandak River

The Gandak River begins in the Nepal Himalayas, emerging from two streams — Kaligandak and Trishulganga. It flows southward and merges with the Ganga River at Sonpur in Bihar.

Ghaghara River

The Ghaghara River has its origin in the Mapchachungo Glaciers and flows down to join the Ganga River at Chhapra in Bihar.

Kosi River

The Kosi River rises north of Mount Everest in Tibet, where it is known as the Arun River. It flows through Nepal and India, often causing floods but also enriching the plains with fertile soil.

Sarda (Saryu) River

The Sarda River, also known as the Saryu, originates from the Milam Glacier in the Nepal Himalayas, where it is called the Goriganga. Along the Indo-Nepal border, it is referred to as the Kali or Chauk, and it eventually joins the Ghaghara River.

Mahananda River

The Mahananda River originates from the Darjeeling Hills and joins the Ganga River in West Bengal as its last left-bank tributary.

Son River

The Son River rises from the Amarkantak Plateau and serves as a major south-bank tributary of the Ganga River, joining it at Arrah in Bihar.

Yamuna River System

The Yamuna River is the largest tributary of the Ganga River with course length of 1376 km. It originates from the Yamunotri Glacier near the Bandarpoonch Peak in Uttarakhand and joins the Ganga at Allahabad (Prayag). The Yamuna has right bank tributaries like Chambal, Sind, Betwa, and Ken and left bank tributaries like Hindon, Rind, Sengar, Varuna, etc. with the Tons River being the largest. The Yamuna’s catchment area spans across Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh.

Chambal River

The Chambal River originates near Mhow in the Malwa Plateau of Madhya Pradesh. It is well known for its distinctive badland topography, forming the famous Chambal ravines.

Damodar River

The Damodar River drains the eastern Chota Nagpur Plateau and flows through a rift valley between Hazari Buag and Chota Nagpur Plateaus, before joining the Hoogly River near Howrah. Its main tributary is the Barakar River.

Brahmaputra River System

The Brahmaputra River System constitutes another vital part of the Drainage system of India. It originates from the either Chemayungdung glacier or Angsi Glacier near Mansarovar Lake in Tibet, very close to the sources of the Indus and the Satluj, where it is known as Yarlung Tsangpo, where Rango Tsangpo is the major right bank tributary. Flowing eastwards across Tibet for nearly 1,200 km, it bends sharply around Namcha Barwa peak and enters Arunachal Pradesh through a deep gorge, taking the name Dihang or Siang.

Within India, it is joined by several tributaries such as the Dibang, Lohit, and Subansiri, forming the mighty Brahmaputra. Flowing through Assam, the river develops a broad alluvial valley characterised by frequent floods, shifting channels and rising of levees or silt deposits. It forms many riverine islands in Assam; Majuli, the world’s largest inland river island, with it being bordered by the Subansiri River to its north and the Brahmaputra River to its south.

In Tibet the river carries a smaller volume of water and less silt as it is a cold and a dry area, whereas, In India, it passes through a region of high rainfall and carries a large volume of water and considerable amount of silt.

After entering Bangladesh, it merges with the Ganga (Padma) and finally The Tista river joins the Brahmaputra on its right bank in Bangladesh, where it is known as the Jamuna (not to be confused with Yamuna River). Which further joins Padma River (Ganga), finally joining an east-drained river Meghna (fed by Barak river through Assam) before draining into the Bay of Bengal through the Sunderban Delta.

Lohit, Dibang (Sikang), BurhiDihing, and Dhansari are left bank tributaries, whereas Subansiri, Kameng, Manas, and Sankosh are right bank tribuatries in India.

The Drainage system of India in the north-east, represented by the Brahmaputra basin with total course length of 2900km with only 916km covered in India, differs markedly from other regions.

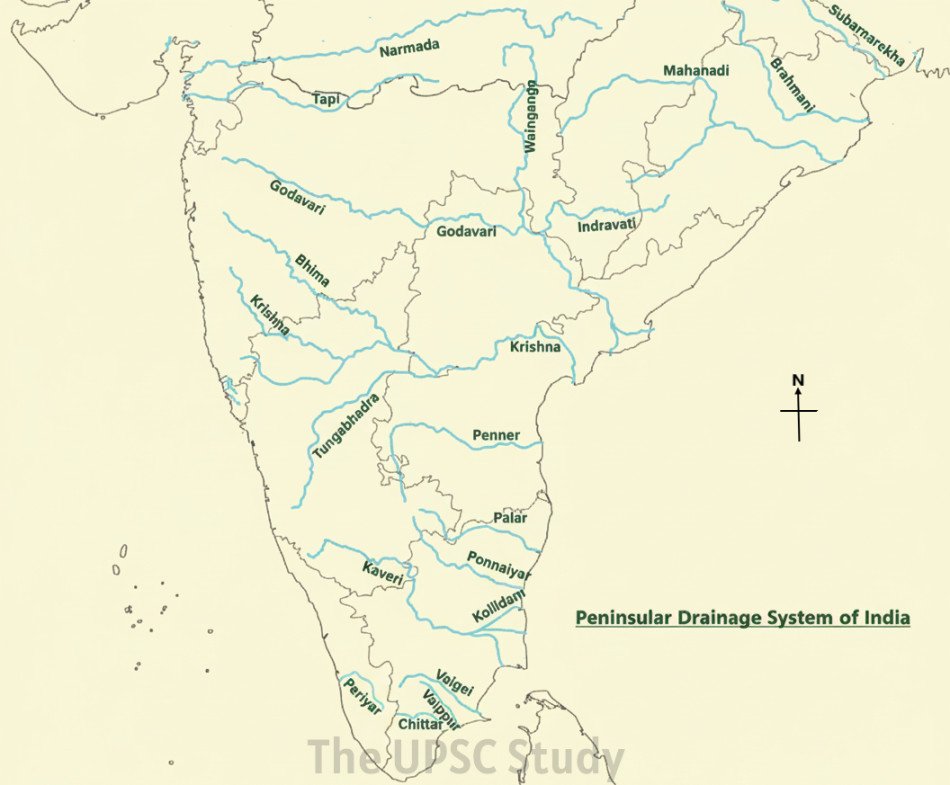

Peninsular Drainage System

Drainage System of India–South

The Peninsular component of the Drainage system of India is among the world’s oldest river networks, carved into a stable geological foundation dating back to the Precambrian era. In contrast to the dynamic, youthful Himalayan rivers, the Peninsular rivers are mature, stable, and largely non-perennial.

The slope of the Peninsular plateau is eastward about 200-300 m inclination, causing the majority of rivers to drain into the Bay of Bengal, while a few such as Narmada, Tapi and Periyar flow westwards into the Arabian Sea. The east-flowing rivers generally form deltas, whereas the west-flowing rivers form estuaries because of their shorter courses and steep gradients.

The major rivers forming this segment of the Drainage system of India include the Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, Kaveri, Periyar, Vaigai, Narmada, and Tapi. the Western Ghats (Shyadri) is the main Watershed divide in Peninsular Drainage system of India. as headwaters of many peninsular rivers are from Western ghats.

According to geological context that the Sahyadri–Aravalli axis, representing the linear stretch of the Western Ghats and Aravalli Range, once served as the primary watershed divide of the Indian subcontinent when the Peninsular region was originally part of the ancient Gondwana landmass, with the Western Ghats positioned centrally on the Dharwar Craton.

During the early Tertiary period, the western portion of this landmass submerged into the Arabian Sea as the Himalayas began to rise. The collision of the Indian Plate and its eastward tilting caused extensive faulting, subsidence, and the formation of rift valleys (horst and graben structures) between the Bundelkhand and Aravalli cratons in the Central Highlands.

As a result, west-flowing rivers such as the Narmada and Tapi began flowing through these rift valleys, which lie between the Vindhya and Satpura ranges.

Characteristics of the Peninsular Drainage System of India

- Reduced eroding capacity: Unlike Himalayan rivers which form V-shape valley at the upper course due to high vertical eroding capacity, the vertical erosion in peninsular rivers is almost negligible and horizontal or lateral erosion takes place forming U-shape valleys by widening of channels.

- Old and Mature Rivers: The rivers are older than the Himalayas and have well-adjusted courses with minimal tectonic disturbance.

- Non-Perennial Flow: Being primarily rain-fed, these rivers show seasonal variation in discharge, swelling during the monsoon and diminishing during dry months.

- Short and Direct Courses: Compared with Himalayan rivers, Peninsular rivers are shorter and flow directly into the sea.

- Well-Defined Valleys: The rivers have narrow valleys with steep sides, reflecting their prolonged erosion into hard crystalline rocks.

- Absence of Meandering: The lack of lateral erosion prevents the development of large meanders or ox-bow lakes.

- Concordant type: Peninsular drainage is mainly Concordant (the river course follows the terrain path) except for some upper peninsular rivers and some places have superimposed and rejuvenated drainage patterns with waterfalls, like Jog, Sivasamundram, and Gokak.

These features make the Drainage system of India in the Peninsular region structurally controlled, stable, and largely independent of glacial or tectonic influences.

Major River Systems of Peninsular Drainage system of India

Mahanadi River System

The Mahanadi, one of the prominent east-flowing rivers, originates near Sihawa highlands in Chhattisgarh. Traversing about 860 km, it flows through Odisha before draining into the Bay of Bengal. The Mahanadi basin supports extensive irrigation and hydropower, particularly through the Hirakud Dam — one of the largest earthen dams in the world.

Tributaries like the Seonath, Hasdeo, Mand, and Ib add to its discharge. Left bank tributaries- Seonath, Hasdeo, Mand and Ib.

Right bank-Jong, Ong and Tel.

This river exemplifies the east-flowing characteristic of the Peninsular Drainage system of India, forming a broad delta near Cuttack and Paradeep.

Godavari River System

The Godavari, known as the Dakshin Ganga or Ganga of the South, is the longest river of Peninsular region and second largest in the total drainage system of India. Originating near Trimbak in the Nashik district of Maharashtra (which covers the 50% of its total drainage basin), further flowing eastward across the Deccan plateaus in Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Andhra Pradesh for about 1,465 km before entering the Bay of Bengal, forming a delta at Rajahmundry.

Purna, Indravati, Sabari, Shivana, Pench, Dharna, Pranhita, alongwith Penganga, Wardha, Wainganga as major left-bank tributaries; and Pravaha, Manjira, Maner, Mula, Peddavagu, Kinnerasani, Sindhphana, Nasardi as right bank tributaries.. The Godavari basin, covering parts of Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh, forms an integral part of the Drainage system of India.

Krishna River System

The Krishna River System originates from Mahabaleshwar in the Western Ghats of Maharashtra and travels nearly 1,400 km before reaching the Bay of Bengal. Important tributaries are the Koyna, Bhima, Musi, and Tungabhadra (formed by Tunga and Bhadra rivulets). Right bank tributaries are Venna, Koyna, Dudhganga, Ghatprabha, Malprabha, Tungabhadra; Left banks are Bhima, Dindi, Peddavangu, Halia, Musi, Paleru and Munneru.

The Krishna basin forms an essential portion of the Drainage system of India, covering large tracts of Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh. The river supports numerous multipurpose projects such as the Nagarjuna Sagar and Srisailam dams.

Kaveri River System

The Kaveri, another key river of the Drainage system of India, originates at Talakaveri in the Brahmagiri hills of Karnataka. Flowing through Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, it drains into the Bay of Bengal at Poompuhar after a course of about 800 km.

Major tributaries include the Hemavati, Shimsha, Arkavati, and Bhavani. Right bank tributaries- Kabini, Suvarnavati, Bhavani, Noyil, Amravati, Moyar and Laxmantirtha. Left bank tributaries- Harangi, Hemavati, Shimsha, Arkavati, Sarabanga and Thirumanimutharu.

Known for its sacred status and fertile delta, the Kaveri is vital to the agrarian economy of southern India, with key irrigation projects like the Mettur and Krishnarajasagar dams.

Narmada River Systems

The Narmada and Tapi are the principal west-flowing rivers of the Drainage system of India.

Narmada: Originates from Amarkantak Hills in Madhya Pradesh, flowing westwards for about 1,312 km through a rift valley between the Vindhyan and Satpura ranges before emptying into the Arabian Sea. Along its journey to the Arabian Sea, it forms several scenic spots such as the Marble Rocks near Jabalpur, where the river cuts through a deep gorge, and the Dhuandhar Falls, where it forms river plunges over steep rocks. The tributaries of the Narmada are relatively short and meet the main river almost at right angles.

The Narmada Basin spans Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, serving as a traditional boundary between North and South India. Flowing through Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Maharashtra, the river finally drains into the Arabian Sea near Bharuch district in Gujarat.

Left bank tributaries: Burhner, Banjar, Sher, Dudhi, Tawa, Goi, Karjan, Kundi

Right bank: Hiran, Tendoni, Barna, Kolar, Uri, Hatna, Orsang, Man.

Tapi River Systems

Tapi: Rises in Madhya Pradesh and flows parallel to the Narmada for about 724 km before joining the Arabian Sea near Surat in Gujarat. Originating from the Satpura Ranges in the Betul district of Madhya Pradesh, it drains regions across Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Gujarat. Its main tributaries include the Waghur, Aner, Girna, Purna, Panzara, and Bori rivers. The coastal plains between the Western Ghats and the Arabian Sea are narrow, which makes the west-flowing rivers like Sabarmati, Mahi, Bharathpuzha, and Periyar relatively short in length.

Both rivers illustrate the structural control of the Drainage system of India, as their westward flow follows fault lines created by ancient tectonic movements.

Comparison between Himalayan and Peninsular Drainage Systems of India

| Feature | Himalayan Drainage System of India | Peninsular Drainage System of India |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Formed after the uplift of the Himalayas; includes antecedent rivers. | Older than the Himalayas; formed on the ancient Peninsular plateau. |

| Nature of Rivers | Perennial — fed by rainfall and glacial melt. | Seasonal — primarily rain-fed. |

| Course | Long, meandering, forming large floodplains. | Short, direct, with deep-cut valleys. |

| Tectonic Activity | Active; frequent course changes due to uplift. | Stable; minor structural adjustments. |

| Landforms | Gorges, meanders, ox-bow lakes, deltas. | Estuaries, waterfalls, residual hills. |

Both systems, though distinct, complement each other hydrologically and ecologically, forming the composite Drainage system of India that supports agriculture, ecosystems, and civilisation across the subcontinent.

Conclusion

The Drainage system of India epitomises the nation’s physical diversity and geological evolution. Encompassing both the young Himalayan rivers and the ancient Peninsular streams, it forms a unified hydrological network that sustains life across varied landscapes. The northern rivers, born in snow-clad peaks, provide perennial flow and fertile alluvial plains, while the southern rivers, sculpted through ancient plateaus, nurture stable agricultural zones through monsoonal waters.

Together, they shape the country’s climate interactions, agricultural productivity, and cultural heritage. The Drainage system of India not only determines the pattern of landforms and vegetation but also influences patterns of settlement and economic activity. However, increasing pollution, over-extraction, and climate variability now pose serious threats to this delicate system.

Ensuring the health of the Drainage system of India demands integrated river-basin management, ecological restoration, and sustainable water governance. Preserving this intricate network is essential for maintaining India’s environmental resilience and securing its socio-economic future.